Stokes State Forest

Click on image to open in lightbox

In 1907, the New Jersey Forest and Park Commission purchased 5,432 acres of land in the northwestern corner of the state and named its Stoke State Forest in honor of Governor Edward Stokes, who had donated the first 500 acres. Some of the tracts included in the original purchase were acquired for $1.00 per acre. Subsequent acquisitions have slowly increased the total land area to its present size of over 16,447 acres. Stokes State Forest is managed as a multi-use forest with the primary functions of protecting the natural resources while serving mankind at the same time.

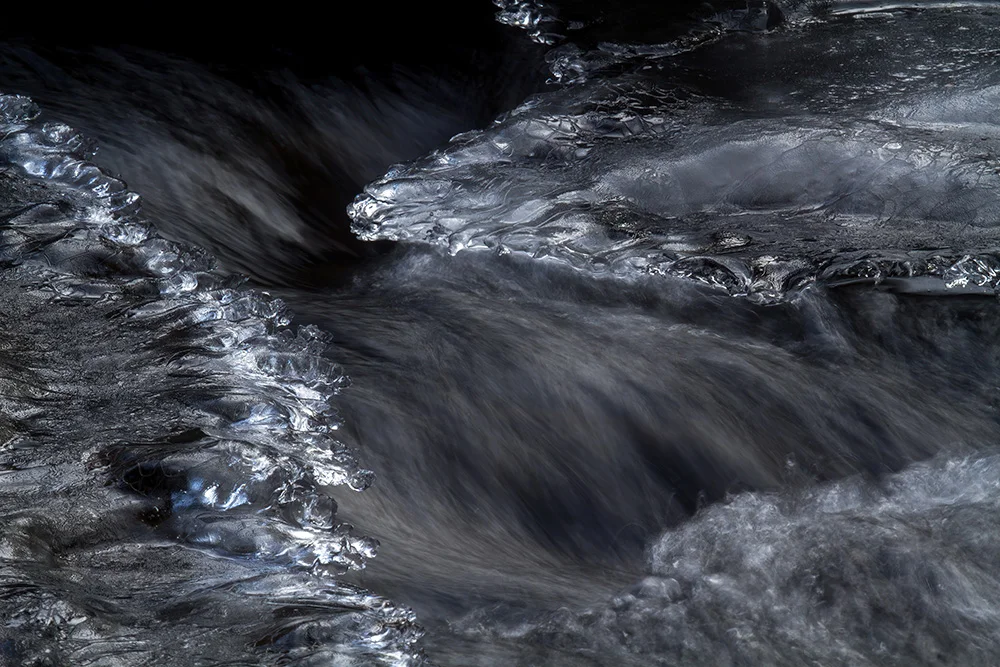

Within its boundaries lie some of the finest mountain scenery, clearest freshwater streams, and natural scenic areas in the Garden State. The area is enriched with history, abounds with a vast diversity of flora and fauna, and offers many forms of recreational activities. (“A Guide to Stokes State Forest”, New Jersey State Park Service, 1982)

Click HERE for info on things to do in the park.

A Guide to Stokes State Forest

Information below comes from A Guide to Stokes State Forest

All photos copyrighted by Dawn J. Benko

Download Stokes Trail Map

History

Stokes State Forest is steeped with history, and the effects of man’s activities are evident everywhere. Long before the first Europeans journeyed into the region, Lenni Lenape communities coexisted with the wildlife that abounded in the forest. The Minsi (wolf) clan inhabited the land which is now called Stokes State Forest. They used fertile areas for small gardens, growing crops such as maize, pumpkin and tobacco and used the forest clad mountains for hunting bear, wolf, deer, and wild turkey. Large centers of native activity were located along the Delaware River and its tributaries.

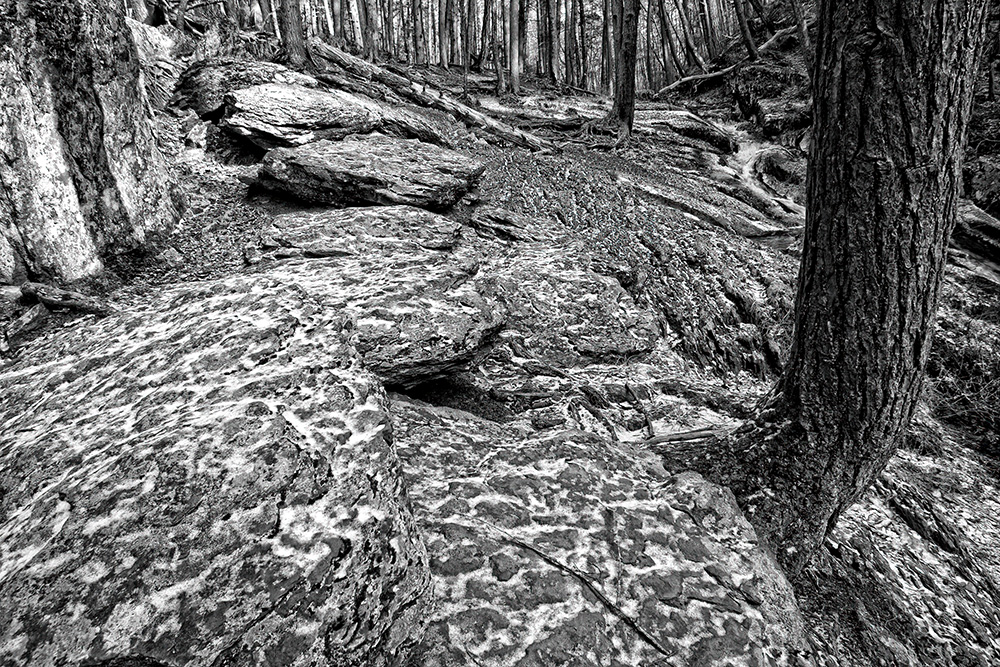

It was not until about the early 1700’s that people of English and Dutch extraction were known to have farmed the area. These pioneers burned vast areas of agriculture and cut the stands of virgin timber for its lumber. Miles of stone fences, foundations, overgrown fields, dams, and root cellars can be seen throughout the woodlands and along the winding brooks of Stokes State Forest. Some of the early homestead sites are marked only by a single stone wall, a depression in the ground, or rotting chestnut fence rails.

An early legend, which has not been documented, states that Dutch pioneers were the first Europeans to explore the area that is now Sussex County. The Dutch, originally seeking copper deposits, found a more valuable blend of iron, zinc, and manganese. Legend also has it that in 1650, Dutch engineers constructed the first highway in the new world—the Old Mine Road—extending from Esopus (Kingston), New York, to the mining site near the Delaware Water Gap in Pahaquarry, New Jersey.

Climate

Less than 10,000 years ago, the area known as Stokes State Forest was buried beneath several thousand feet of glacial ice, making its climate very similar to that of Greenland today. As the ice melted and retreated northward, the area was characterized by mean annual temperatures below freezing, strong winds, and permafrost. The summer months had temperatures averaging above freezing; however, there were many fluctuations above and below the freezing point and a continual cloudy sky with frequent sleet and snowstorms. Gradually, the climate became warmer and drier until it reached a maximum, some 2000 years ago. Since then, the climate has cooled and become somewhat more humid. Scientists have accurately recorded these climate changes by analyzing pollen samples from the bottom of swamps and bogs in the area.

Today, the mean annual temperature of the area is 48°F with extremes ranging from -32°F to 103°F. The growing season is 220 days long, lasting from April 4th to November 10th. The frost-free season is 150 days in length and lasts from May 7th to October 4th. The annual rainfall equivalent is 44 inches, and the annual snowfall is 55 inches. On many occasions 15 to 25 inches of snow falls in a single storm. During July and August, the wind is from the southwest but blows from the northwest the remainder of the year.

Physiography

Stokes state forest is located in what is called the Ridge and valley province, a term used for an area exhibiting mountain ranges, valleys, plateaus, and rock outcrops. The Ridge and valley province extends from the Saint Lawrence river lowlands through New Jersey and Pennsylvania and continues for a total span of 1,220 miles before ending in northern Alabama.

Locally, the province is composed of the Kittatinny Valley to the east and the Delaware Valley to the West, the two being separated by Kittatinny Mountain. The Kittatinny Range starts about 10 miles southwest of the Hudson River, near Kingston, New York, and rises abruptly as an almost unbroken escarpment of the Shawangunk conglomerate. The ridge varies in elevation, with its highest point in New Jersey being 1,803 feet above sea level in High Point State Park. In places, the mountaintop is a double crested Ridge, with the topography of the eastern slope being several hundred feet higher and more rugged than the western crest. At other times the ridge top exists as a plateau nearly four miles wide. The eastern face of the ridge drops abruptly into the Kittatinny Valley while the western phase has a more gradual slope into the Delaware Valley. As the range nears the Delaware Water Gap, the ridge becomes narrow and single crested.

Geology

Bedrock Geology

Stokes State Forest is underlain by two major geologic formations, both of which date back about 400 million years. The eastern section consists of Shawangunk conglomerate, a mixture of white quartz and reddish, slate pebbles embedded in a grayish silicate matrix. The conglomerate, sometimes called pudding stone, forms the crest of Kittatinny Mountain and its steep rocky southern slope. Excellent examples of the conglomerate can be observed along the Appalachian Trail, which leads to the summit of Sunrise Mountain.

West of the ridge crest, the forest sits upon the High Falls formation, consisting of alternating red-green and olive colored sandstones and shales. In the higher elevations, the softer red shales predominate, with the top layer being concealed by varying thicknesses of glacial till. The lower beds of the High Falls formation contain red quartzitic sandstones. Transition from Shawangunk to the High Falls is not sharply defined but occurs very gradually. Excellent examples of the High Falls formation can be observed in the rock outcrops along Coursen Road and in Tillman Ravine.

To the east of Stokes State Forest, the Kittatinny Valley is underlain by two basic geologic formations, Cambrian age Kittatinny limestone and Ordovician age Martinsburg shale. Northwest of Beemerville at the base of Kittatinny Mountain lies an eroded dike of nepheline syenite. The volcanic syenite occurs along the contact zone between the Martinsburg shale and Shawangunk conglomerate formations.

To the West of Stokes state forest lies the Delaware Valley with early Devonian period formations of limestone, sandstone, and shale predominating.

The chronological order of geomorphic events which occurred in this area is as follows:

- 600 million years ago: The Kittatinny limestone was formed by lime-secreting algae living in a warm shallow sea. The limestone deposits covered the Pre-Cambrian formations found in the present day Highlands region of New Jersey.

- 500 million years ago: the Martinsburg shale was formed from several thousand feet of silt that subsequently drifted into the sea burying the beds of limestone.

- 450 million years ago: the land was uplifted out of the sea, exposing the Martinsburg formation. This upheaval required enormous amounts of heat and pressure that originated from the earth’s inner core.

- 440 million years ago: The Shawangunk conglomerate was formed by deposition and of sand and gravel material from streams, thus covering the shale beds.

- 420 million years ago: encroachment of a very shallow sea onto Shawangunk caused deposition of silt by feeder streams. Some of the debris was also deposited above sea level on land similar to that of present-day tidal marshes. The layers of silt combined to make up the High Falls formations.

- 400 million years before ago: During the Devonian Period, a warm, shallow, coral sea filled with many lime-secreting organisms formed the limestone beds that lie beneath the Delaware Valley to the west of Stoke State Forest

Formations were deposited horizontally and later subjected to intense heat, pressure, and mountain building forces. They were complexly folded, faulted, tilted, and uplifted into mountains that were as high as the Rockies of today. Approximately 80 million years ago, erosion reduced these mountains to a flat, even surface known as the Schooley Peneplain. From the summit of Sunrise Mountain, one can see the remnants of this peneplain in the even-crested topography of the Highlands region to the east and the Poconos to the west.

A massive vertical uplifting of the peneplain occurred approximately 60 million years ago. Since that time, differential erosion by water, wind, and ice have created the topography of the region as it is today.

The formations in the New Jersey Ridge and Valley Province exhibit a northwest-southeast tilt so that the farther one travels from the southeastern border of the forest, the younger the area in terms of geologic history.

Glacial Geology

During the last million years Stokes State Forest was covered by three different continental glaciers, the most recent being the Wisconsin, which traversed Kittatinny Mountain approximately 10,000 years ago. As the ice sheet advanced south from the Hudson Bay region, it worked a twofold operation on the landscape. First, it cut down much of the land and rock strata by erosion; second, it built up other areas with scoured material deposition. The material which was pushed forward and left behind when the glacial ice receded is called till. Most of Stokes State Forest is blanketed with varying thicknesses of glacial till-up to 100 feet in depth-with the thickest deposits occurring West of Kittatinny Mountain in the Flatbrook Valley region.

The topography was further altered by the floodwaters of the melting ice sheets. These streams and rivers eroded material and translocated it to other areas. Water deposited material is called stratified drift, the various sizes in the layers being determined by the volume and velocity of water involved. Although little stratified deposits exist in the forest, some can be found along the big Flatbrook.

The final alteration of the landscape during the Ice Age resulted from the many cycles of freezing and thawing of the soil. Generally speaking, the frost action tended to smooth out many surface irregularities by moving loose rocks and boulders down slope.

Vegetation

Stokes state forest lies in the transition zone where the central forest formation of oak and hickory overlaps and begins to give way to the northern forest formation of beach, Birch, Maple, and hemlock. In such areas, local environmental conditions, particularly microclimate and soil, influence the types of vegetation found. Normally, there will be progressive changes in ground cover and forest type from ridgetop to stream valley.

Seven different forest types can be found throughout the immediate area and each is briefly described:

- Pitch Pine-Scrub Oak

The pitch pine-scrub oak community occurs on ridge tops where there are numerous rock outcroppings, a thin dry soil layer, and a very harsh climate, which is characterized by high winds and extreme temperature fluctuations. The pitch pines are widely spaced and average about 18 feet in height, exhibiting broken tops, twisted branches, and gnarled trunks. The scrub oaks are smaller in height, usually growing less than 10 feet tall and often forming a dense thicket. Sheep laurel is often found growing beneath the scrub oak canopy layer. Red maple and black birch are found in those stands where there is sufficient moisture for their survival

A pitch pine-scrub oak stand can be observed on the summit of Sunrise Mountain, surrounding the lookout shelter.

- Pine-Oak

The pine oak community occurs on the hilltops west of the Kittatinny Ridge. The pitch pines are the largest and tallest individuals in the stand. The oaks-white, scarlet, and chestnut-are the most abundant tree species but are all smaller in size. Black gum and sassafras are also present in small numbers in the understory.

The pine oak forest cover type is rather restricted in size. One of its narrow ranges exists on Crigger Road, 0.3 to 0.6 miles north of the Grau Road-Crigger Road intersection. - Chestnut Oak

The chestnut oak community is by far the most commonly found forest type in Stokes State Forest, covering about 75% of the total area. Red oak is usually the co-dominant species, with fewer numbers of black oak, hickory, and black birch in the lower levels. You will notice more than one large chestnut oak growing from a single stump; these are sprouts which grew from trees that were cut between 75 and 100 years ago. American chestnut sprouts are also common in the understory. Chestnut was abundant prior to the blight attack of 1904.

A well defined region of chestnut oak domination can be observed along Sunrise Mountain Rd. north of Stony Brook trail (0 to 0.4 miles). - White Oak-Hickory

The white oak-hickory community is found on the more moist and fertile soils within the forest. The best stands are developed on old farm fields and the Big Flatbrook Valley. Other trees that might be found in the stand include red oak, chestnut oak, red m Weirdaple, hickories, and American beech. These stands are usually not of sprout origin but instead are good examples of natural regeneration.

Stands of white oak and assorted Hickory species exist along Coursen Road. - Mixed Oaks-Hardwoods

On some sites there is no single dominant tree species but rather a general mixture of many varieties of trees. In this forest cover type, white oak, red oak, white ash, red maple, and sugar maple are the most common trees. Others growing at the site include hickories, beech, black gum, Tulip Poplar, chestnut oak, black oak, black birch, scarlet oak, and chestnut sprouts. These communities are found on the lower slopes and adjacent valleys where soils are deep and rocky and where abundant moisture drains down slope.

A good example of this type of forest is located along Coursen Trail in the vicinity of its intersection with Stony Brook. - Mixed Northern Hardwoods Without Hemlock

This forest type is very restricted in its distribution; it is best developed in northwest facing coves and stream valleys. Often, much of the stand is flooded during the spring when melting snow and rain cause the streams to overflow their banks. The trees typically found are sugar maple, beech, yellow birch, and occasionally white pine, basswood, red oak, and black birch. American chestnut was also once abundant prior to the blight of 1904. The forest cover type is common in the New England states and explains why the maple syrup industry and Yankee Clipper shipbuilding industry were important.

An example of this forest type is found along Tuttle Brook on the northwest side of Shotwell Rd. for 0.2 miles starting at the bridge by the Stokes State Forest maintenance yard. - Mixed Northern Hardwoods with Hemlock

The forest cover type with hemlock is usually restricted to the steep, rocking northwest facing ravines. The most common species found our eastern hemlock, yellow Birch, and rhododendron. Black Birch, sugar Maple, white pine, beach, and bass wood can also be found on the upland slopes.

In addition to Tillman ravine, a mixed northern hardwoods with hemlock stand can be found along Sunrise Mountain Rd. approximately 0.7 miles north of its intersection with Upper North Shore Rd.

In addition to natural diversity, the vegetation patterns of Stoke State Forest have been modified by the past activities of man. Natives often set fire to the land to facilitate hunting and farming. With the arrival of European man, the areas suitable for agriculture were cleared of trees and shrubs and were plowed. Wood was in great demand for domestic and industrial fuel as well as for rough planking, railroad ties, and logs for building construction.

With the dawn of the industrial revolution, exploitation of the forest resource was intensified, with conversion of wood into charcoal. The discovery of iron deposits in nearby Franklin and Andover placed great demand on the forest, since charcoal was the principal source of energy to smelt iron ore in the blast furnaces. In the year 1855, 63,000 cords of wood or 6,500 acres of prime hardwood forest were burned for the iron industry alone. Standing timber was felled regardless of size or vigor, and by 1865 the region was completely denuded of vegetation.

During the late 1850s and early 1860s, the majority of the cast iron was forged into lengths of rail which ironically led to the demise of charcoal making in this area. The railroad connected the rich anthracite coal fields in eastern Pennsylvania with iron furnaces and the major industrial cities, supplying both with the inexpensive and seemingly endless supplies of fuel.

The early farmers and homesteaders also used charcoal and charcoal soot. The dust was used as toothpaste, for water purification, storage of ice, in the making of gunpowder, packing of meats, and in building of roads. Although almost everyone made charcoal for home use, the charrering of larger amounts was considered a fine art-the vocation of a select group of men known as charcoal burners. These burners were responsible for charring the mounds of logs until only the wood ash remained.

Nature and man have since combined efforts to reforest the region period from 1919 to 1942, the state Forest Service and the Civilian Conservation Corps planted 652,765 trees of 20 different varieties on the abandoned farm fields and open spaces within Stokes state forest. The seedlings were planted in rows and have grown up into many plantations that can be seen scattered throughout the area. 7 significant and unusual cover types have resulted from these efforts and an example of each with its respective location are listed below.

- Red pine Planted 0.2 miles west of the StrubleRd/ Rt, 206 intersection

- Southern white cedar Located in the southwest corner of the red pine plantation

described above - Norway spruce Located on the South side of grow Rd. just north of the

entrance to lake Ocquittunk camping area - White pine Planted along Kittle Rd. just north of the entrance to the

group camping area - Japanese larch Located on the South side of Rt 206, approximately 0.2 mi

south of the Struble Rd./Rt. 206 intersection - Chinese chestnut Found directly opposite the larch plantation described above

on the north side of Rt 206 - Scotch pine Located on the north side of gravel Rd. Approximately half

way between the entrance to lake Ocquittunk and cabin #16

Several plantations of Douglas fir, a species indigenous to the Pacific Northwest region, were planted. However, the majority of the stock failed to adjust to the climate, soil, and other growing conditions and, subsequently, only a few scattered individuals remain alive today.

Many stands of native trees over 100 years old can be found in Stokes State Forest because nature did not wait for man’s intervention. As soon as a farm was abandoned or forest sight was otherwise disturbed, vegetation began to quickly invade the area and soon established themselves.

Wildlife

The woodlands, streams, lakes, ridges, and open spaces within Stokes state forest provide a variety of habitats for a vast diversity of wildlife, both seasonally and year round. Kittatinny Ridge, with its loose rocks, ledges, and bold rock outcrops, provides den sites for hibernating snakes such as copperhead and rattlesnake. Located along the Atlantic flyway, Stokes also serves as a resting area for many transient, migratory bird species. Thousands of raptors and geese can be seen in the fall from Sunrise Mountain, attracting scores of wildlife observers and photographers annually.

In the valley regions, shallow Beaver ponds along the Flatbrook and its tributaries provide a haven for flycatchers, herons, woodpeckers and their prey. Woodchucks and field mice abound in open areas. Coniferous woods shelter porcupines, red squirrels, kinglets, and many other animals, while the deciduous forest habitat serves white tailed deer, rabbits, wild Turkey, and many species of woodland birds. These are but a few examples of the diversity in habitats that one can find in Stokes state forest.

When hiking along the trails and stream banks in the forest, Please remember that you are a guest and practice active conservation. Never disturb a nesting site or destroy natural vegetation upon which wildlife depend for food and cover.

Anthropic History

Stokes State Forest is steeped with history, and the effects of man’s activities are evident everywhere. Long before the first Europeans journeyed into the region, Lenni Lenape communities coexisted with the wildlife that abounded in the forest. The Minsi (wolf) clan inhabited the land which is now called Stokes State Forest. They used fertile areas for small gardens, growing crops such as maize, pumpkin and tobacco and used the forest clad mountains for hunting bear, wolf, deer, and wild turkey. Large centers of native activitiy were located along the Delaware River and its tributaries.

It was not until about the early 1700’s that people of English and Dutch extraction were known to have farmed the area. These pioneers burned vast areas of agriculture and cut the stands of virgin timber for its lumber. Miles of stone fences, foundations, overgrown fields, dams, and root cellars can be seen throughout the woodlands and along the winding brooks of Stokes State Forest. Some of the early homestead sites are marked only by a single stone wall, a depression in the ground, or rotting chestnut fence rails.

An early legend, which has not been documented, states that Dutch pioneers were the first Europeans to explore the area that is now Sussex County. The Dutch, originally seeking copper deposits, found a more valuable blend of iron, zinc, and manganese. Legend also has it that in 1650, Dutch engineers constructed the first highway in the new world—the Old Mine Road—extending from Esopus (Kingston), New York, to the mining site near the Delaware Water Gap in Pahaquarry, New Jersey.